April 27, 2021

Adam Price

Tags: GPS Interference, Multipath

When you can no longer see your drone, how can you trust it will continue to operate safely and accurately? And how can you prove to aerospace regulators that it’s capable of safe and accurate independent navigation?

These are vital questions for UAV developers, service providers and operators as regulators start to approve use cases that see drones flying beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS).

They’re questions I explored in depth in a recent webinar with Inside GNSS and Inside Unmanned Systems, along with expert speakers Okko Bleeker of OFB Consult and Howard Loewen, President of UAV autopilot developer MicroPilot.

You can watch the on-demand webinar Preparing for Increased PNT Dependence for UAVs Beyond Visual Line of Sight or learn more in a summary of the key points below.

BVLOS will be a natural evolution as drones are put to more uses

The coming years will see increasing use of drones in areas like survey, emergency response, parcel delivery and infrastructure inspection, with Market Research Future predicting that the worldwide UAV market will grow to $75bn by 2025.

Many of these use cases will only be truly valuable if the drone is approved for BVLOS flight. An emergency response drone, for example, will be most valuable if it can fly to an accident site ahead of first responders, and start sending video that can help them prepare.

To gain BVLOS certification, developers and operators of UAVs will have to meet exacting standards for safety and reliability. Proving the accuracy and reliability of the drone’s autonomous navigation system will be a key requirement.

Designing reliable guidance, navigation and control (GNC) systems for UAVs

In his presentation, Okko Bleeker draws on decades of experience in aviation systems engineering to explain the design principles behind a robust and accurate guidance, navigation and control (GNC) system for a drone or other unmanned aerial system (UAS).

He looks at factors that should be taken into account when defining a reference trajectory for each mission, and the positioning, navigation and timing (PNT) technologies available to developers to ensure the UAV follows its intended route.

Some of the key considerations covered in his presentation include:

“If we lose the GNSS engine for reasons of multipath or spoofing or anything [like that], then we might lose control of the aeroplane.” – Okko Bleeker, Senior Consultant, OFB Consult

Understanding and mitigating against GNSS vulnerabilities

In the Spirent presentation, I review the critical role played by GNSS in obtaining an accurate position, before exploring some of the ways GNSS reception can be compromised, including:

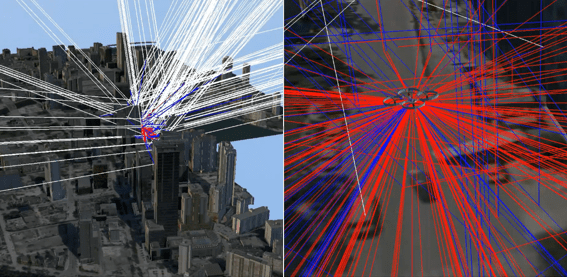

Simulated 3D model of UAV in Downtown Miami – multipath signals (in red and blue) can cause a UAV to miscalculate its position if not accounted for in the GNSS receiver design.

There are several ways to test GNSS receivers and UAV navigation systems to understand how they handle vulnerabilities like these. In my presentation, I recap the main methodologies and provide some pointers for choosing the right type of test approach.

Testing UAV autopilot systems in the lab at MicroPilot

The final presenter is Howard Loewen, who, as president of MicroPilot, has designed and developed UAV autopilot systems used by over 1,500 companies worldwide.

“When we make our safety case to the regulators, they’re used to seeing aerospace-grade arguments and failure probabilities. If we come with design processes that are more suitable for laser printers, they’re going to be naturally nervous.” – Howard Loewen, President, MicroPilot

He explains what aviation regulators look for in terms of safety evidence and failure probabilities for unmanned aircraft and sets out a three-step process for demonstrating that a UAV meets appropriate safety standards.

As the third step in the process is to collect test data to show that failure mitigation measures work, he goes on to show how MicroPilot conducts performance tests on its autopilot systems.

This involves extensive simulation (using a Spirent simulator to generate realistic GNSS signals), as the live signal environment isn’t controllable or repeatable, making it impossible to assess the true impact of any design modifications. As Howard points out, it’s also impossible to test the receiver’s handling of events like the GPS week number rollover in advance without a simulator.

Howard also provides some good insights into using lab simulation to gather performance data from months of flying, to investigate possible corner cases, and to conduct over-the-air testing of the UAV’s GNSS antenna system using an anechoic chamber.

Get more BVLOS advice and insights

The webinar attracted a large audience from commercial and military organisations around the world, who had some very good questions for the panel. If you have any interest in designing, developing, integrating or certifying BVLOS navigation systems for UAVs, it’s one not to be missed.