April 1, 2021

Tags: GPS Interference, GSS9000, High Dynamics

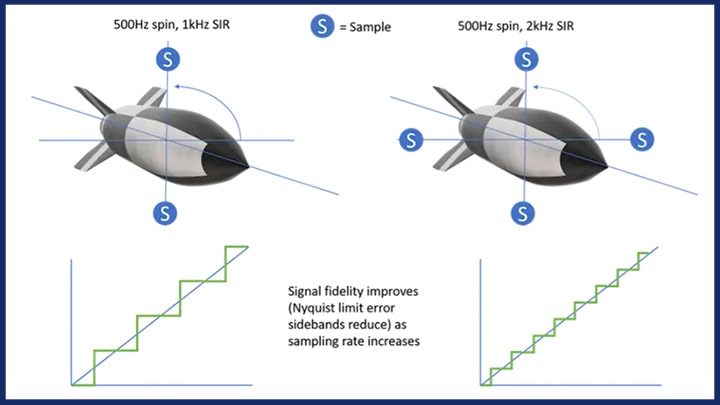

For testing PNT systems in a high-dynamics environment, such as rockets, guided munitions and even some UAVs, a realistic reproduction of that environment requires a lot of quick looks. A very great lot. The high speeds, acceleration and jerkiness of the platforms mean that solving simulation discrete models as frequently as possible becomes critical to ensure that the simulated trajectory closely reproduces a real-world one. Spirent’s GSS9000 simulator provides both hardware and software updates of 2 kilohertz, that is, once every half a millisecond.

For testers, this means higher realism in the vehicle models that they are running: significantly better accuracy of simulation results, mimicking the realistic conditions to which the sensors and antennas aboard the platforms will be subjected. Were the updates to be only 1 khz, once every millisecond, the vehicle’s simulated movement might appear jerky, and deviate in meaningful ways from the true path.

“The more points you add to the trajectory that you are generating in the simulator, the better fit you will have to the real trajectory. This is an extra value to the customers,” says Ricardo Verdeguer Moreno, product line manager for high-end applications at Spirent Communications.

It also produces a lower latency rate for hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) and faster conversion from digital inputs to RF analog outputs. “Some customers use a simulator to generate the vehicle dynamics, for an aircraft for example. They send all the PVT information to the simulator, the simulator has to read the message, apply it to the simulation and then generate the RF signals on top of that. By doubling the update rate, we are making all the steps in this process much faster, so we decrease the overall latency of the HIL system.”

As example, he cites missiles, quite jerky with a lot of lateral acceleration. “At a 1 khz rate, the path could look perfectly straight, but at 2 khz you see that you have some deviations from that straight line, so you have some factors to consider for your sensors.”

As another example, Moreno cites drones, which can be quite “twitchy.”

“They have a lot of noise in the trajectory, they hover in their positions, they are quite unstable in general. In simulation, the vehicle could look more stable than it really is. When you get into solving the models in a more accurate way, you realize it is not accurate.”

Adam Price, director of PNT simulation at Spirent, adds, “We’re seeing more and more applications where a customer will feed in the trajectory of their UAV into our simulator. They have their own model of how that vehicle moves from point A to point B, and the jerk can be fairly rapid there. We want to make sure that our simulator is not holding it back, not creating latency or “slurring” it, to make sure we’re not creating any kind of impairment in the simulation.”

“We’re trying to solve the PNT position for the customer,” resumes Moreno. “We are talking about reaching centimeter accuracy. To achieve that level, it’s quite important to have real representation of the trajectory. For a missile, a small acceleration pattern could actually generate a position difference of tens of meters, for vehicles moving at such velocities. Those milliseconds or halves of milliseconds at those velocities, that can mean a few centimeters that will have an impact at the end on your PNT solution.”

A key principle of simulation is making sure the simulator is superior to the device under test.

“One thing is the update rate of the simulator and the other is that of the receiver. Even if the receiver update rate is slower than the simulator, it will generate some errors.”

“It’s a fair assumption that a great number of the customers are using IMUs,” says Moreno, “which update at a much faster rate than the GNSS. So, we’re enabling those customers to have a more realistic simulation.”

For simulators in these cases, it’s important that to have a capability for a rapid GNSS simulation rate and to also have the capability for fast reading of the inertial sensor’s data rate. The simulation rate cannot be a dominating factor in the performance of the simulation.

Currently, activity in the space sector is at a rapid increase, with significant investment in placing assets in orbit, whether that’s low-Earth orbit or higher. Satellites from commercial customers are going up at an almost staggering rate. When those satellites, carrying GNSS receivers and inertial sensors aboard the launch rockets, when they get vertically launched, they go through tremendous rates of acceleration, and they spin a lot as well. “This is another application where we want to be able to simulate that for our customers,” says Moreno. “It’s not limited to the military defense world; commerce applications are a bigger and bigger challenge .

Spirent’s 2 kHz works on the latest GSS9000 model, the third generation of that line. Updates are available to double the rate at a software and a hardware level, in the same simulator that customers currently have. Spirent has also introduced a trade-in policy for older versions of the 9000. “We are making sure that no one stays behind.”

Spirent’s multi-element controlled reception pattern antenna (CRPA) test system, built around the GSS9000 platform, offers:

This article was first published on Inside GNSS.